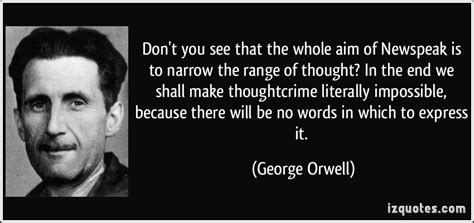

Newspeak Racism

.jpg)

Malila sensed the ground tremble in a bowel-loosening crescendo. Small stones bounced in the dust at her feet. She looked up into the oncoming terror, bizarrely shaped animals with huge forequarters tapering to slender hips and massive misshapen heads covered in horn and dark fur. They bore down on her with wild eyes and lolling tongues, arcs of spittle flicking across their flanks. Into the chaos, the old man sprang up, flapping a hide and ululating across the prairie in a clear, high voice.

The herd veered off, circled back to a small clearing, and slowed. Malila knelt and aimed at one of the smaller animals. The crack of the pulse rifle echoed back from the trees. The animal dropped to its knees before falling to its side. The herd set off again, charging along the edge of the woods and returning to the wider reaches of the grassland. After she could no longer feel the shuddering throb through her feet, she ran to the kill site, arriving just as an exultant Jesse did.

The old man scooped her up and spun her around. For an instant Malila, transported by her success, enjoyed Jesse’s delight, feeling his strength elevate her face into the warm autumn light. They stopped laughing, and the old man let her slip down and out of his grasp. Malila had enough time to realize how her body stroked along Jesse’s before her feet once more found the ground.

“Wonnersome shooting, lass. I dinna think ah seen better.”

It was only then Malila appreciated just how enormous the beast was, the chest coming almost to her shoulder. Jesse took the pulse rifle from her, put it back into his pack, slipped his long knife out of its sheath, and set to work. He stripped to his waist, rectangular tattoos absurdly contrasting his pale skin. Jesse cut a long gash in the animal’s belly and began pulling armfuls of steaming entrails out of the bloody cavern. Malila was predictably queasy.

They left the carcass, minus tongue, hide, haunch, liver, and shoulder, to the wolves and ravens. Improvising a sledge from the hide and springy saplings cut from along the tree line, they made good time, pulling in tandem until the sun was almost down. Jesse had them bathe when they found a stream and then abandon the sledge. He cut a few long green branches from a tree, and they hiked into the forest along the stream. They camped that night at a bend with a wide sandy beach.

Jesse, using the short knife, cut a generous circle of the raw bison hide, wiped the blade, and flipped it to her so that the handle hit the ground at her knee.

“Strip the bark off those branches, lass. We are going to have a delicacy.”

Malila finished her task in time to watch Jesse finish pegging the bloody hide to the ground and start to scrape it free of flesh and hair with a tool from his kit. She was fascinated, not for the first time, by the delicate handling and deft touch he used on what was, to her, a foul and bloody souvenir.

“Now make a loop out of each branch, the ends together,” he called to her.

Once scraped clean, the old man folded the raw hide into a more or less flat-bottomed cone and fastened the loops of green wood around the edge, folding the edges of the hide under one and then over the other. Pouring some water into the bottom of the cone, he placed it into the fire.

“Why bother with all that if you were just going to burn it, old man?”

“Watch and learn, lass.”

Some of the residual fat rendered and flamed, sending up a spiral of oily smoke. Malila expected the whole thing to incinerate at any moment. Jesse, building the fire up around the cone and adding water, remained unperturbed. When the cone was about half full and the water boiling, he threw in some salt and a handful of weeds that he had harvested along the stream. Then he lowered a portion of the skinned bison tongue into the cone, the water rising perilously close to the rim.

When she did not respond, he added, “Admit it, lass: it’s a neat trick, doncha think? Water boils and keeps the skin too cool to burn. The handles catch the hide between them and keep the shape to hold the water. The hide cooks into shape to keep the handles together. So I got a boiling pot.”

“For an old man, you are such a little kid.”

“One of my many endearing qualities, lass.”

Within minutes, Malila inhaled a savory smell. Jesse hoisted the piece of tongue out and carved the coarse meat crosswise into slices. For the first time in weeks, Malila’s mouth watered. He offered her the first slice, and she grabbed it, the flesh tender, hot, and sweet. The tang of the seasonings gave a relish where hunger had provided appetite. She chewed it briskly before swallowing, waiting for Jesse to offer her another slice.

They spent the evening eating tongue while the old man sliced the haunch and jerked it over the fire. For the first time since her capture, Malila experienced an odd sensation of satisfaction. Together they had brought down a great animal and were sharing in the success of their efforts.

“I want to commend you, lass. You took down a moving buffalo. You are a better shot with that weapon than I could hope to be.”

“Thank you, Jesse. I am, aren’t I?”

He gave her a smile, a genuine smile, and Malila saw the young man Jesse must have been once. Without much thought she asked, “Why do you have all those tattoos?”

“They mean things to people as know how to read them.”

Malila placed three fingers next to her nose and drew them down and away from her. “What do those mean, then?”

Jesse raised a hand to his face, touching the blue stripes absently. “They tell people that I’ve killed three men, righteously.”

“In war, I suppose.”

“No, not in war.”

“Then it was murder.”

“No, lass. Jury saw it as righteous. The way you tell, Lieutenant, for future reference is if I were a murderer, you’d not see me at all. We can’t afford to have murderers around isolated farms with kids for the taking. If we catch one, he dies.”

“What if he gets away?”

“Then we don’t see him at all. If we do, it’s shoot on sight, no jury, thank you. If we find a body, then a jury sits to decide if it was a righteous killing or not. Righteous, it earns you a mark, so that people know you on sight. Killing changes a person, righteous or not.”

“But three?”

“I amn’t going into the tales for your titillation, my young friend, but one was a man who I shot in the back as he was running away.”

“You shot him in the back? You could have let him live!”

“I could have. He left behind the body of my wife and was dragging away my daughter, perhaps I might have mentioned.”

His whisper came to her from a distance she could not see. Malila’s chest tightened spasmodically. She knew no children other than her distantly remembered younger self and her friends. She had no vocabulary for sorrow, no words for regret, pain, or loss. The Unity’s response to loss was rage and scorn. Malila reached out to touch the old man’s hand as it cupped his knee. She had failed to express her feelings, unnamed as they were. Jesse started as she touched him, coming back from years and miles away, pulling his hand away from her. Her sudden flow of tears surprised her.

Jesse pressed one of his red handkerchiefs into her hand as Malila struggled to calm her breathing and distance herself from this unseen quicksand of emotions.

“You must have done something terrible to earn the big tattoos on your back then!” She smiled, handing back the handkerchief, making it a statement.

Jesse explained to her another odd practice of the outlands. He pulled up his tunic near the warmth of the fire to display one and then another of his decorations. The oldest, smallest, and most faded tattoo was his graduation certificate from a secondary school. Even so, it was meticulous, elaborate, signed, and numbered. By outlander standards, Jesse was an accomplished scholar. Degrees in engineering and medicine were duly exposed, admired, and discussed.

“What is a doctor of medicine?” Malila blurted as the last one was explained. This tattoo occupied the upper portion of his right chest, ornate with curlicues and shadings.

“You don’t have any doctors in the Union?” exclaimed Jesse. “Who takes care of the sick?”

“An HP—health care provider. You get a doctorate of government or philosophy but not health care. No one gets a doctorate in that.”

Jesse tapped the blue patch reflectively. “Getting that was painful … and the tattoo wasn’t much fun neither! Family tradition and all.”

“I thought you were raised in a hollow by your parents.”

“I was. Both of my parents were docs, but they were hiding out when the Union attacked us. It wasn’t for years they felt safe enough to come down. If the Union didn’t shoot you, the hunger mobs would find where you holed up. The militias didn’t make it really safe until I was half-grown. My folks both had the teaching gene as well, it seems. By the time I was twelve years old—that’s when we came out of hiding—I started my sophomore year in high school. My sister and her family still live in St. Lou.”

“Why not just put the certificate on paper?” asked Malila, truly fascinated despite herself.

Jesse shrugged. “People skin is cheaper than sheepskin, I ’spect. My parents had all theirs on parchment. After the Meltdown and the Scorching, people had to be a lot more mobile. Big cities like Chicago burned. Detroit was leveled, first by the rebels and then by the Canadians. Anyway, people started inking themselves to prove they had done what they claimed they had. No worries about getting your papers burned or lost and no worries if the city where you went to school was a smoking hole in the ground.”

“So you are marked for life. You can’t go anywhere without everyone knowing who you are and what you’ve done?”

“Why would I want to, lass?”

The idea was chilling. In the Unity’s crowded streets, Malila felt like a stone in a stream, unremarked amid the citizens sliding around her. The people were supreme in their will but anonymous in their persons.

Jesse offered her another piece of bison tongue on the tip of his long knife. She moved closer to the old man, feeling his warmth as they shared the bounty.

‹ Back